My interest in this entry is to

articulate an existentialist reading of the Dishonored

video game series, with particular reference to the philosophical work of

Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness.

This entry will likely include

heavy spoilers for this series.

Dishonored is a video game series developed by Arkane Studios and currently consists of three main instalments (Dishonored,[i] Dishonored 2,[ii] and Dishonored: Death of the Outsider),[iii] the first of which has two DLC components (The Knife of Dunwall and The Brigmore Witches).

The narrative unfolds within the empire of Gristol, a setting

largely based on 19th century Britain. As we experience it, Gristol

is a city of decadence and corruption, with swarms of lethal rats haunting the

streets, weepers spreading a deadly disease and with most of the citizenry

living in abject poverty whilst the wealthy nobility grow fat in their palace.[iv]

Within the gamespace, the player takes up the role of an assassin[v]

whose mission is to amend or avenge a wrong that has been dealt to them. The

first instalment has us become Corvo Attano, the Royal Protector of Empress

Jessamine Kaldwin who is killed mere minutes into the game. Wrongly accused of her

murder, Corvo then joins with a loyalist conspiracy to avenge the death of his

Empress (and lover) – rescuing their daughter Emily along the way. The second

game follows much the same format – though this time one can either continue

playing as Corvo or instead take up the role of Emily, now an adult – with the

role of the villain being none other than Delilah,[vi]

the Empress’s estranged sister, who has returned to claim her throne, at Emily’s

expense.

| A portrayal of the Outsider by Tumblr User wroniec |

The narratives of the series’

various instalments are all influenced by the ephemeral figure of the Outsider.

Towards the beginning of each story, the protagonist will find themselves

awakening only to immediately be beset by the feeling that something is not

quite as it should be. Upon venturing from their room, they will find

themselves in an infinite expanse of darkness, littered with motes of earth

suspended in the black. Then, the black-eyed Outsider will appear from nothing,

welcoming them to the Void. Through the course of this meeting, the protagonist

will receive the Outsider’s mark, a symbol on the back of their left hand,

which allows them to channel the power of the void into the world. This unlocks

a host of supernatural powers[vii]

that the player can then use the navigate the game world, circumvent enemies,

or which can simply serve as tools of destruction.

Each game then proceeds as a series

of missions, wherein each mission tends to follow the same general formula. You

must navigate an area that is largely filled with guardsmen (or other enemies

that are out to get you) in order to locate and either ‘kill’ or ‘neutralise’ a

single ‘target’. No level can be completed if the target is not dealt with but

ultimately the game takes a ‘play your way’ strategy. You are given the tools

but ultimately you must decide how to use them. Players can choose to simply

charge in, cutting down the guards and wielding their magical abilities to

wreak mayhem or they could opt for a quieter approach. Indeed, the game rewards

the player with an achievement/trophy (depending on your console) if they can

complete the entire game without killing anyone, and an additional trophy if

they can complete the game without being seen. The game operates on a high/low

chaos system, whereby the more death and confusion the player causes, the worse

of a state the world will be in by the conclusion of the story.

It is my contention that Dishonored creates a game space which is

attending to questions of choice, meaning and individuality as raised within

existential philosophy. In particular, I see this in how the series treats the

concept of nothingness.

The cosmology of the Dishonored universe is built upon the

Void. The Void underlies the world and serves as a foundation to all existence. The Heart (an artefact capable of whispering secrets to the protagonist throughout the game) says of the Void that it "is the end of all things. And the beginning". Human beings are thought to arise from the Void and to return to it upon death.

Though there is no clear eschatology, the peaceful dead are spoken of as fading

away into the oblivion of the Void, whereas the tumultuous souls seem to remain

very much themselves within the infinite expanse of nothingness.

Within the

narrative, the Void is attributed many qualities, but in particular is thought

to be in some sense conscious. Indeed, the Outsider himself serves the role of

being the mythological ambassador or avatar of the Void, fundamentally a part

of its structure. As we see in missions such as ‘A Crack in the Slab’, the Void

is usually separate from the world, though anomalies may occur wherein the Void

slips in, overcoming the strict boundaries of time and place.

The philosophy of French

existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre uses nothingness as a central concept within

his framework. For Sartre the individual subject is fundamentally negative

because this subject is conscious and consciousness for Sartre is nothing.[viii]

A consciousness is not an entity or a substance, nor is it an object, but is

instead nothingness. Of course, consciousness can have content – but this does

not mean that the consciousness itself is a positive being in any meaningful

way. The only content possessed by consciousness are its experiences, which are

understood as intentional – here meaning that they pertain to things or

entities that are outside of the consciousness itself. For Sartre,

consciousness is a hole in the world[ix]

– much like a void that slips into the world in order to overcome or transcend

it in some way – which is to say, to negate the world.

|

| The French Existentialist Philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre |

For Sartre, the nothingness of

consciousness is its fundamental structure, as well as the foundation of

individual human freedom. For Sartre, freedom is absolute. We are always free,

absolutely and completely free, in every circumstance. This is to say that our

behaviour cannot be meaningfully said to be determined, for the individual

consciousness is not an object but an absence[x]

and as such cannot be part of traditional causal picture. The only limit upon

this freedom is an internal one, wherein we are condemned to be free such that

we are unable to get beyond our own freedom.

Importantly, freedom for Sartre

is not to be confused with instrumental power.[xi]

In this sense, to be free is not to be able to do anything that one wants,[xii]

but is instead an existential freedom concerned with the kinds of projects one

can commit oneself to. One is always able to devote oneself to whatever project

with whatever ends/outcomes one may wish, and though this does not guarantee

one’s success, the ability to achieve one’s projects does not impact that these

projects are necessarily free. To this end, the projects that one pursues are

always freely chosen and there is not necessity for one to pursue anything in

particular. This would amount to attempting to abdicate from one’s own freedom,

to live in bad faith[xiii]

– which for Sartre can never succeed. As such, Corvo is free to devote himself

to a project of revenge or to a project of reconciliation – to become a deadly

assassin and thus to leave the streets of Dunwall running red with blood or to

instead stay his hand and take not a single life.[xiv]

For Sartre, projects are

fundamentally to be understood through the structure of action – which is

(perhaps unsurprisingly, given the theme of this piece) to be understood as a

form of nothingness.[xv]

This is not to say that actions are themselves nothing, or that actions cannot

produce positive results, but that actions are fundamentally attending to negativities

(négatités). When one acts, one is

responding to a lack within the world – to something that the world is not yet

that the individual wishes it to be. By recognising that what they want is a

negativity in so far as it does not exist[xvi]

and by then recognising that the state of the world is also a negativity in so

far as it can be transcended or overcome[xvii]

in such a way as to amend this lack, the individual is able to commit an action

to this effect. Even action that is fundamentally concerned with creating

something new is, at least according to Sartre, concerned with overcoming the

state of the world as one that lacks the object that is to be created.

Dishonored seems to play upon this distinction between one’s

absolute freedom and the instrumental power to bring about the ends of one’s

chosen projects through the figure of the Outsider. Though the dominant

religion within the Empire, The Abbey of the Everyman,[xviii]

preach that the Outsider is a devilish figure, the Outsider does not exist to

torment or to tempt individuals into committing sinful/evil acts. Though he is

portrayed as a Luciferian character, the Outsider could be better compared to

the Norse trickster God Loki.[xix]

But even this comparison implies a malicious intent or even a connotation as

simple as deception. The Outsider is neither of these, he never misdirects and

seems to only ever speak the truth, though appears to want to reveal uncomfortable

truths more readily than others. Central to the games’ narratives is that the

Outsider bestows you with supernatural powers and abilities, many of which are

fundamentally violent in nature, but he never forces your hand to use them.[xx]

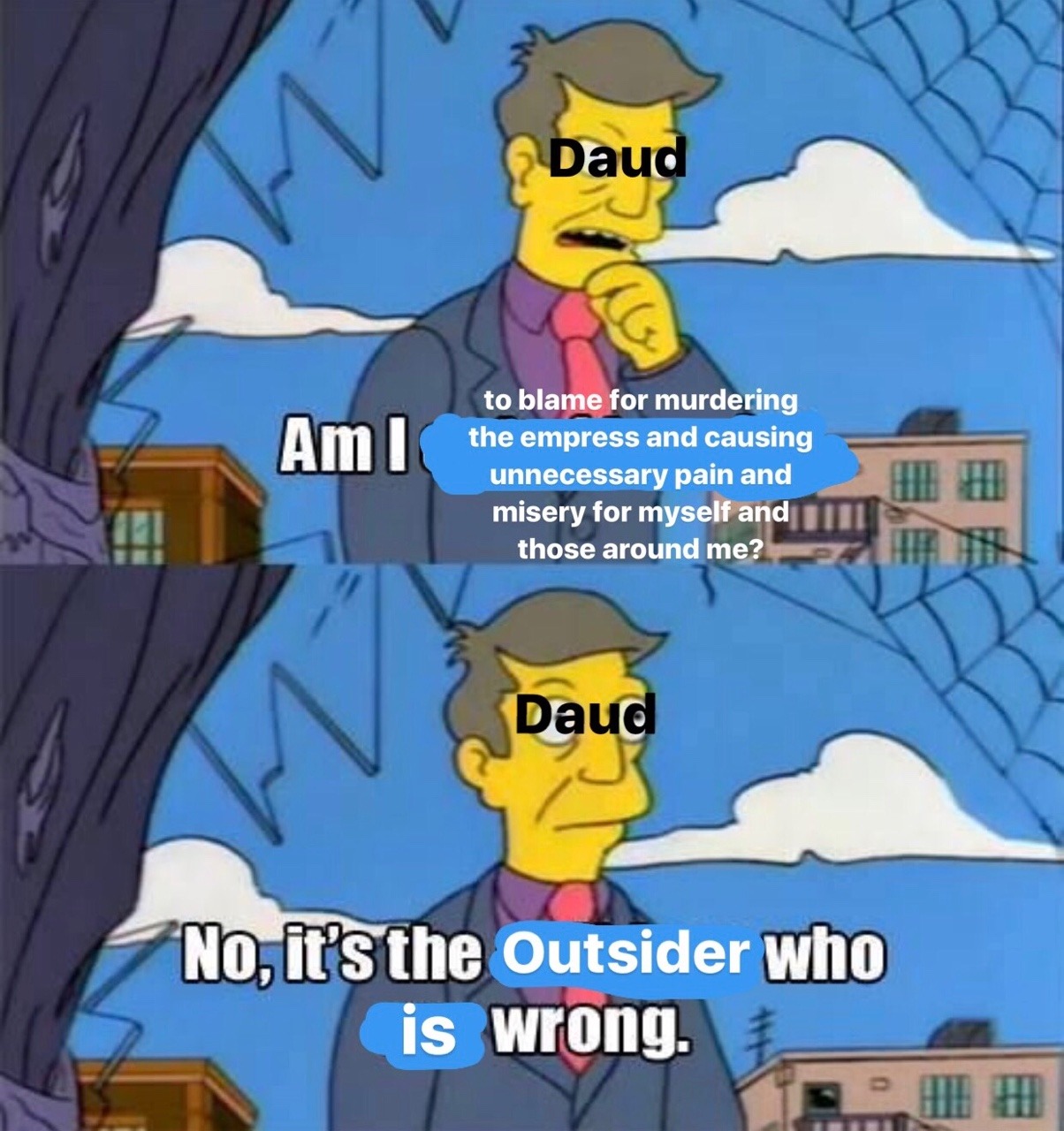

Thus we can see that when, in Death of the Outsider, Daud attempts to

blame the Outsider for all the horrors plaguing Gristol,[xxi]

he is fundamentally trying to ignore not only his own responsibility as a user

of the mark, but also the foundational freedom of every individual who

possesses such power. Through so ignoring the free agency of all involved, Daud

is living in a state of bad faith, attempting to posit the Outsider as a

determining cause for all the terrible things that happen across the course of

the series. But the truth is that the Outsider cannot solely be to blame. All

he provides it greater power which is to say nothing, and he does not do so at

the expense of anyone’s existential freedom as this is absolute, regardless of

the situation in which the agent finds themselves.

| An edit of the assassin Daud by Tumblr user Winterswake |

We can clearly see how the mark

of the Outsider (and the powers that it grants) play into this structure of

action as negativity when we consider the fundamental cosmology of Dishonored’s universe. When the

protagonist uses the power of the mark, their powers are manifestations of the

Void within the world. The power of the Void, which is nothing, is thus to be

summarised as negativity. As such, the supernatural powers granted by the

Outsider’s mark constitute novel ways in which its user is able to negate the

world around them. Powers such as ‘blink’ negate space, allowing the

protagonist to partially overcome it, just as ‘Bend Time’ reorients the

character’s relationship with temporality.[xxii]

This increases their individual power to fulfil or realise their projects,

through an increased ability to transcend or negate the state in which they

find the world. Importantly, this does not increase their freedom – as on a

Sartre’s view freedom is always absolute and cannot be increased or diminished.

This is the case even when the protagonist uses powers such as ‘possession’, which

allows them to control their foes for a brief period of time. Though it greatly

reduces the power of the target, and possibly interrupts their consciousness,

it cannot be said to limit their freedom.

| The Mark of the Outsider as it appears on Emily's hand. |

Though Dishonored’s game space is limited in terms of what can be realised

within it (though one might ask if the same could not be said of life itself),

its gameplay and narrative proceed in a manner that can clearly speak to

Sartrian notions of consciousness and action – in so far as these are linked

through the concept of nothingness. Dishonored

presents us with a fundamentally existentialist narrative not only in so far as

the player/protagonist alone must bear the burden of their own freedom, but

also in so far as every single ‘target’ they are called on to either

assassinate or spare must bear theirs. In most cases, the assassination targets

have committed or been complicit within terrible acts – such as murdering the

empress and overthrowing her daughter (in the case of most of the targets in

the first instalment) – and sure enough they may have their reasons. But

fundamentally – they have chosen to be who they are. Whether they know it or

not, whether they want to face it or not, each of them has committed themselves

to a fundamental project of becoming who they are.

But the question then becomes –

what fate does the protagonist think they deserve and, following whatever

course of action they take, what kind of person has the player chosen to be?

I’ll leave you with the words of

Billie Lurk, who inadvertently summarises the existential choice when she says:

“Then you’re alone, living with your choices.”[xxiii]

|

| Also, this image is simply too good not to include. Posted by Tumblr user boyokiddo |

Works Cited

Colantonio, Raphael, and Harvey Smith, Dishonored (Arkane

Studios, 2012)

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Being and

Nothingness, trans. by Hazel E. Barnes (UK: Routledge, 2003)

Smith, Harvey, Dishonored 2

(Arkane Studios, 2016)

———, Dishonored: Death of the Outsider

(Arkane Studios, 2017)

[i] Raphael Colantonio and Harvey Smith, Dishonored

(Arkane Studios, 2012).

[ii] Harvey Smith, Dishonored 2 (Arkane

Studios, 2016).

[iii] Harvey Smith, Dishonored: Death of the

Outsider (Arkane Studios, 2017).

[iv] I

am further interest in how Dishonored

constitutes (or fails to constitute) a reading of historical imperialism, but

this is not my concern within this entry.

[v]

Though for reasons we shall see, this is perhaps too violent a term.

[vi]

Originally, Delilah’s character was introduced in The Knife of Dunwall DLC, and she serves as the main antagonist of The Brigmore Witches. In neither case is

the story directly concerned with the experiences of Corvo or Emily, with the

assassin Daud taking up the protagonistic position.

[viii]

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and

Nothingness, trans. by Hazel E. Barnes (UK: Routledge, 2003), chap. The

Origin of Negation.

[ix] “The

For-itself, in fact, is nothing but the pure nihilation of the In-itself; it is

like a hole of being at the heart of Being” see: Sartre, chap. Conclusion.

[x] Sartre, p. 434.

[xi] Sartre, pp. 469–88.

[xii] Sartre, p. 453.

[xiii]

See: Sartre, chap. Bad Faith.

[xiv]

Indeed, existentially speaking Corvo is free to devote himself to whatever

project he wishes. The game space is limited in that ultimately only one of two

projects (or a combination of these two projects) can be realised. Though this

point does not weaken the game as an example of existentialism so much as it

highlights that there are limits upon one’s ability to fulfil one’s projects.

[xv] Sartre, pp. 433–34.

[xvi] Sartre, p. 435.

[xvii]

Sartre, p. 435.

[xviii]

There is a sense in which, if we take the Outsider as in some sense an agent of

the existential project, that the Abbey and its Overseers serve as

representatives of bad faith within the narrative. Their religion is centred

around strictures and limits, which are often exalted as being beyond our

ability to choose against – thus their beliefs actively appear to endorse a bad

faith avoidance of existential choice. This is further supported by the idea

that the Overseers are enemies of the Void, which on this reading is the

structure of existential being.

[xx]

The Outsider does occasionally nudge and play games with his marked, such as

when he encourages Daud to seek out Delilah, but his interventions in no way

undermine another’s agency.

[xxi] Smith, Dishonored: Death of the

Outsider.

[xxii]

In Death of the Outsider, Billie Lurk’s

‘Foresight’ ability enables her to negate both time and space at once.

[xxiii]

Introductory cinematic, Smith, Dishonored: Death of the

Outsider.

No comments:

Post a Comment